Welcome to the sixth and final installment of 2020 in our Grower’s Spotlight series! This is a bit unconventional because the “grower” we’re featuring isn’t a grower at all! Rather a master of compost, Mike Sturges created and has been stewarding the Stanton Heights Community Composting Program for over a decade now. Grow Pittsburgh Master Composter students visited the site earlier this summer as part of their coursework and walked away with a wealth of knowledge from Sturges, who uses a rapid hot composting process, known as the Berkeley Method. He’s hopeful that his program can inspire others to “pick up a pitchfork and figure out how they can make Pittsburgh more sustainable”. Interested in learning more about starting a compost project like this in your own neighborhood or community? Read more on the Stanton Heights program below and reach out to Mike to learn more!

GP: When did you first start composting and what’s been your experience since then?

Mike: I grew up about 20 minutes north of the city in a much more rural area. Our kitchen scraps went to our chickens. We added our leaves directly to our garden as well as chicken manure. Brush was typically set to the edge of the property or used as kindling for our wood burning stove. When I purchased my house in Stanton Heights in 2009 I wanted to remove some shrubs. I asked a neighbor next door what people did with landscaping debris and he answered, “Wait until there aren’t any cars coming, carry it across the street and dump it over the hill in the greenspace.” I went and looked over there and sure enough, there were leaves, grass, brush, beer bottles, flower pots, old fencing, tires, old lumber and concrete… lots of concrete. I had been sitting on the board of Allegheny CleanWays for two years at this point so I knew that I wanted to clean up the dumping to prevent further dumping of non-natural items. I wondered if moving forward if it’d be possible to get people to only dump natural items. From 2009 to 2011, I started to remove some of the garbage out of the existing pile and covertly turned it and used some of the existing compost in flower beds. In 2012, we had our first large scale clean up on the space. The compost heap was legitimized by Comcast when they built wooden bins as a part of a Comcast Cares Day. We call these the compost “finishing” bins because we outgrew the bins before they were built. We don’t really use them now except as a landmark when giving people directions.

GP: To someone who’s never heard of the Berkeley Method for composting before, how does it work?

Mike: When I first started composting in the space, it was really just about composting what was dropped off all together in one pile. It was a lot more manageable as fewer people were utilizing it. I took a more passive approach and I would just remove any non-natural items and let the items sit and the compost could be utilized the next year. Over time, I realized that brush and sticks had no place in a compost heap unless they were turned into wood chips first as they make the pile nearly impossible to turn. When more people started to hear about the space, I started getting more drop offs. It became apparent that things that were obvious to me were not obvious to those dropping off debris, so I began putting extra signage up to direct people and it’s very user-friendly now.

More and more people started asking if I could give them some advice on starting up some sort of initiative in other communities. It was only in others asking me to teach them that I started actually doing research on composting, thinking about what I was doing and growing as a composter myself. Knowing that I’d be having people out for a tour or workshop made me think about how I was doing things more critically. Ultimately, through the volume of items being dropped off combined with an effort to cut down on redundant work, I’ve arrived at my current process using the Berkeley Method.

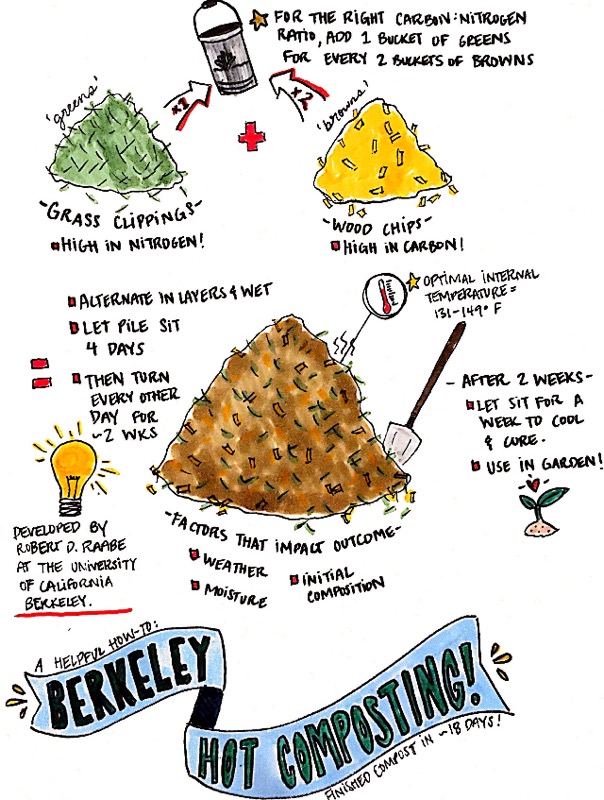

This time of year, we get literally tons of leaves dropped off. From April to October, we literally get tons of grass dropped off every week. The leaves can sit and decompose and no one would be the wiser, but if we do not immediately address the grass, you can smell it from several hundred feet away and this has caused many complaints in the past. Using wood chips donated from Wildmiller Tree Service, I utilize the Berkeley hot-composting method to turn grass clippings into garden-ready compost in around a month. The grass clippings are high in nitrogen and the wood-chips are high in carbon and both are finely chopped up when they come to us. We mix them both, make a large pile and let this sit for four days. After the fourth day, we turn it every other day and turn it for about 2 weeks. Every batch is different and the weather, moisture and initial composition of the pile impact the final outcome but typically after that two weeks of turning we let it sit for a week or so to cool and cure and then it can be used in the garden.

GP: How long have you been doing the community composting? What have been your biggest challenges and successes with it since you’ve started?

Mike: My community composting evolved over the last decade from just cleaning up an illegal dumpsite to trying to provide a service to the community. The biggest challenge continues to be illegally dumped items like concrete and hard-to-compost items like large volumes of brush, which I ask people not to dump on the space. It requires constant monitoring, meeting new people who are utilizing the program and detective work to prevent illegal dumping. I get compliments daily on the compost program and very few complaints (now that we have the smell under control). The reason this program is so utilized is that there is no cost to drop off items and no closing time. Many people are generating landscaping debris on off hours and due to work schedules or not having a vehicle available cannot get them to city drop off centers before they close. As a result many people put landscaping debris out on the curb. Sometimes driving through the city on garbage night, I’ll count dozens of these brown paper debris bags set out by well-intentioned people, unaware that the city only picks up these items at the curb twice a year. We are doing a service both to the people generating the debris, and also to the city by circumventing debris that would end up in garbage trucks and ultimately in a landfill. Neighbors feel good knowing that these items are not going into a landfill and trust the compost from the program as they know what’s going into it.

GP: Approximately how much compost do you produce annually?

Mike: It’s hard to say how much compost we produce annually because people take it on a regular basis. I can confidently say that people took more than 20 tons in 2020 but much of this compost was from 2019 and previous years that we had stored.

GP: What’s the best piece of advice you could give to someone interested in composting but is maybe a bit intimidated?

Mike: Jump in and try it and fine tune as you need to. Don’t get too caught up in trying to follow a compost recipe. Everything organic is going to break down over time; it just may take longer or smell worse. Anything you do by turning a pile is likely going to make it work faster.

GP: Does your “workload” at the composting site vary drastically seasonally? What’s a typical day in the compost consist of?

Mike: The busiest time of year in the compost is late spring though early summer with all of the grass that is dropped off. The second busiest is in the fall due to the large amount of leaves and work keeping the drop off areas open so that items do not pile up too high. I usually check the compost before work each morning and every day when returning from work to triage what items I absolutely need to complete that day. Someone setting a few hundred pounds of debris in the wrong spot may take you 10 minutes to address but if left unchecked for a few days, that could turn into an eight-hour work day if everyone else follows their lead. Most days it is making sure that everything is being added to the right spot and a few quick pile turns.

GP: Approximately how much of your time per week do you estimate you spend composting?

Mike: March through November, I usually spend about 8 hours composting each week. I spent a lot more time in the compost this past spring because I knew that this would be the year when having a lot more compost available to offer to the community would count more than other years as people may be out of work or have extra time on their hand and could use access to free compost to grow food for their families. Also, with the gym being closed, having the compost workout helped me to cope with the additional stress 2020 added to my day job. The end result was a record-breaking year in regard to compost donation and a much more efficient compost operation workflow. As a parent, it was important to my wife and I to have our daughter join us when we work in the space. We added a few swings and have utilized natural items to make the space more enjoyable for her. An unexpected result was that during the early part of the pandemic, people started to utilize the greenspace around the compost as a park. We have been beautifying the space for over a decade and are glad that people have been enjoying it.

GP: Anything else you want to share with us?

Mike: I work with a group of friends to make hard cider, called A Few Bad Apples. We utilize foraged unsprayed fruit to make hard cider to promote sustainability and to help support local nonprofits and community organizations. Since many of our cider events were cancelled in 2020, I was able to spend a lot more time in the compost improving the space and making compost available for the community.

Know another local gardener you’d like to see in the Growers Spotlight come 2021? Maybe it’s you! Drop us a line to be featured in our next newsletter or on our blog.